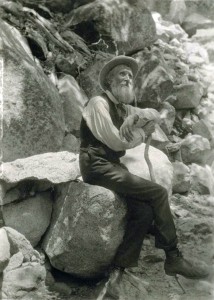

Visiting Yosemite for the first time in the 1980s I was enjoying our week long stay and stopped in the bookstore/gift shop to pick up something to read in the evenings. When I am visiting a place I always like to read something about the local history, so the book that I purchased was “Son of the Wilderness – The Life of John Muir” by Linnie Marsh Wolfe. Until that time I never really knew anything about John Muir (born: April 21, 1838 died: December 24, 1914) and I became fascinated with the life story of the Scottish-born naturalist, author and wilderness preservation activist. He seemed to be such a simple man that was filled with such joy and wonder on his treks into Yosemite and other places of natural beauty throughout the country. To honor his birthday today, this post tells the story of his life and will discuss his many accomplishments that changed the way many of us view our natural surroundings and our desire to save those special places for future generations.

John Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland and was the third child of Daniel Muir and Ann Gilrye who had a large family of eight children. Muir was raised in a very strict religious home and this is probably the reason he was constantly in trouble for his mischievous adventures. He was a curious child exploring the countryside around his home where he developed his love of nature early in life. But his idyllic life in Scotland was soon to change in 1849 when the Muir family immigrated to the United States and settled on a farm located near Portage, Wisconsin.

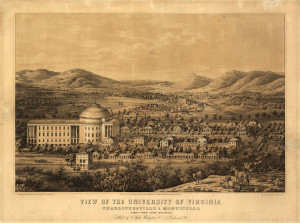

Muir’s father was a very strict and dominating parent who required his children to work hard on the farm and adhere to his deep religious beliefs. When he was 22 years old, Muir finally found some freedom from his difficult life when he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin located in Madison. Muir took his studies very seriously and was proud to pay his own expenses working several different jobs. He was a good student and soon developed a life-long friendship with Professor Ezra Carr who became an important mentor to Muir by inspiring an interest in chemistry, botany and geology and also his wife, Jeanne, who encouraged Muir in his future career as a naturalist author.

Muir never completed his college education and instead followed his brother to Canada in 1863 to avoid military service. While in Canada he spent the spring and summer exploring the area around Lake Huron but when his money started to run out he rejoined his brother in Ontario and soon found work at a local sawmill. In 1866, Muir returned to the United States and settled in Indianapolis, Indiana and started work in a local factory making wagon wheels. He proved a valuable employee and was very inventive in improving the factory’s machines and manufacturing process. Unfortunately in March 1867, Muir had an accident that was to dramatically change his life. While working at the factory a tool slipped and struck him in the eye requiring his confinement in a darkened room for six weeks while he recovered from the injury. During his convalescence, Muir re-evaluated his life and decided that he needed to pursue his dreams of exploration and the study of nature which he felt this was his true purpose in life.

In September 1867, Muir set out on a trip from Indiana to Florida that he later wrote about in his book, “A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf”. His plan called for no specific route, just to wander through the wilderness across the country until he reached his destination. He ended up in Cedar Key, Florida and quickly found work at the Hodgson’s sawmill. Muir traveled briefly to Havana, Cuba to study the flowers and shells of the island and then later traveled by boat to New York to connect with another ship traveling to California.

Arriving in San Francisco, Muir soon made plans to travel to a place he had recently read about and was very anxious to see. On his first visit to Yosemite, Muir was overwhelmed by the beauty of the high granite cliffs, abundant waterfalls and meadows filled with flowers. He eventually found seasonal work as a shepherd in the valley, then at a local sawmill and he built a cabin along the Yosemite Creek where he lived for two years. Muir later wrote a book about his experiences in “First Summer in the Sierra”. While living in Yosemite, Muir would take frequent hikes into the backcountry with a tin cup, a small supply of tea, a loaf of bread and a worn copy of a book of essays by the naturalist author, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Fatefully in 1871, Emerson came to Yosemite while on a tour of the Western United States and Muir was able to meet the author that he so greatly admired.

While living in Yosemite, Muir became known locally for his vast knowledge the natural history of Yosemite and visiting scientists, artists and other distinguished people would hire him as a guide. When he was not working, Muir would often wander about the Yosemite Valley and the surrounding area to learn more about the botany and geology of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He soon formed an interesting theory that the ancient glaciers “sculpted” the valleys and the granite surfaces of the mountains which was contradictory to the accepted scientific theory at the time. Eventually Muir proved that his theory was valid through his observations of an active glacier near Merced Peak and encouraged by his friend, Jeanne Carr, Muir had his findings published in local and national newspapers. Over the years, Muir continued travels in Yosemite and he also ventured to the state of Washington and then into the Alaskan territory of the United States. (Remember, during this time in history Alaska was not officially a state until 1959)

By 1878, Muir’s friends were starting to encourage the constant wandering 40 year old bachelor to finally settle down. Returning to the San Francisco area, his close friend Jeanne Carr introduced Muir to Louisa Strentzel, the daughter of a prominent physician named Dr. John Strentzel. The Strentzel family lived northeast of Oakland on a 2,600 acre ranch filled with fruit orchards in Martinez, California. Then, in 1880 after returning from a trip to the Alaska territory, Muir and Louisa were married. Shortly afterwards, Muir went into partnership with his father-in-law and for the next ten years Muir managed the property and the large fruit orchards. (Travel Note: the Martinez house and a portion of the ranch are preserved by the National Park Service as the John Muir National Historic Site. For more information, please see their website at www.nps.gov/jomu)

Muir and Louisa had a happy marriage and they had two daughters, Wanda and Helen. While living at the house in Martinez, Muir gradually he began to spend an increasing amount of time writing about his experiences not only in Yosemite but also his past trips into the Alaska territory and the state of Washington where he climbed Mount Rainer. For a man that enjoyed spending his time exploring the natural world around him, Muir soon found himself developing a successful career as a naturalist author.

Over the years, Louisa began to fully understand that her husband was becoming more restless in his stationary life at the ranch and he needed to return to his travels. Muir frequently returned to his beloved Yosemite, this time bringing his daughters with him but sadly he began to see the disastrous damage caused by the overgrazing of sheep in the meadows and the effect of the extreme logging of the Giant Sequoia in Mariposa Grove during his absence. It was while on a Tuolumne Meadows camping trip in 1889 with an influential editor of “Century” Magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson, that Muir convinced the editor of the need to bring the Yosemite area under federal protection. Muir and Johnson lobbied Congress and the Act to create Yosemite National Park was passed on October 1, 1890. Unfortunately, the State of California still controled the areas of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove but Muir was successful in persuading local officials to prohibit livestock grazing in the Yosemite backcountry to stop any further damage.

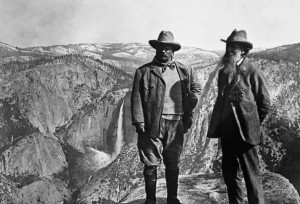

Meanwhile, Muir was approached by Professor Henry Senger of the University of California at Berkeley to attend a meeting that was being held to form a group that was to become known as the Sierra Club. That first meeting was held on May 28, 1892 and Muir was soon elected to be the club’s first president, a position that he held for 22 years. Muir and the Sierra Club continued the efforts to lobby the federal government to include the areas of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove into a proposed expanded Yosemite National Park. During a visit to the California in 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt traveled with Muir to Yosemite where they camped near Glacier Point for three days. During that trip, Muir was able to convince Roosevelt about the need to bring those areas under federal control to protect them from further damage. In 1906 Roosevelt signed a bill increasing the size of Yosemite Park to include both Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove.

Unfortunately, Muir and the Sierra Club were not successful in saving another area of Yosemite. The population and urban growth of the nearby San Francisco area caused a desperate need for an additional water source. Political pressure was mounting to dam the Tuolumne River in the Hetch Hetchy Valley to create a large water reservoir. Muir was very strong in his opposition of the project and united with his fellow members of the Sierra Club, Muir wrote to President Roosevelt about his concerns. Then, President William Taft suspended the Hetch Hetchy dam project temporarily. Muir and the Sierra Club keep the pressure on the federal government and a national debate went on for years regarding the project. Eventually, President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill authorizing the construction of the dam and it became law on December 19, 1913. Muir was greatly affected by the decision and he was deeply saddened by the loss of the Hetchy Hetchy Valley.

Within in a year of the defeat, Muir died in Los Angeles, CA on December 24, 1914 after a brief bout with pneumonia, he was 76 years old. Muir is buried next to his wife’s grave near their former home in Martinez but until recently the burial site was privately owned with limited access. Currently the National Park Service has acquired the grave site and there are plans to include it into the nearby John Muir National Historic site.